|

Rule 68: Can Fee Shifting Work in Employment Cases?

There is no denying that the potential of recovery by plaintiffs of costs and fees in cases brought under federal and state discrimination and wage laws drives settlement of litigated claims. Unless an employer defendant gets a defense verdict, a trial award to a Plaintiff of even a nominal amount will result in recovery of fees and costs by the plaintiff that are likely in excess of $100,000. Juries have no knowledge that a “compromise” verdict of a few thousand dollars for a plaintiff will ultimately result in a judgment for the damage amount, plus a considerable award of attorney fees.

The risks associated with trial in employment law is primarily borne by employers, since there is no recovery of expended fees in the event there is a defense verdict. Plaintiff’s counsel will likely be out fees and costs of litigation in the event of a defense verdict, but the plaintiff him/herself has very limited exposure. The realities of this disproportionate risk results in plaintiffs bringing claims that oftentimes have little or no evidentiary support, without any real risk for pursuing frivolous claims. He/she is no worse off after litigation, even if there is a defense verdict. However, an employer has already expended considerable defense costs and fees to be proven correct.

Even in a case where there is potentially some issue with liability for the employer, but where the plaintiff has a very limited damage number, it can sometimes be difficult to settle cases. Plaintiff’s attorneys sometimes agree to “split” the finally-awarded amount (judgment plus fees), resulting in little incentive for a plaintiff to accept a settlement offer that covers their limited damages – in the hopes that there is a bigger payout by taking the case to trial and sharing in the award of fees.

There are not many tools that an employer has to try to level the playing field. One option for consideration is an early offer of judgment utilizing Rule 68 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. This tool will not be right for every case, but is something worth considering.

While Rule 68 offers may result in recovery of fees and costs pursuant to offers of judgment under Title VII claims, the FLSA, ADA, and ADEA never permit a defendant/employer to recover attorney fees - only allowable costs. When a defendant’s Rule 68 offer of judgment is rejected and the plaintiff receives a lower judgment at trial, the plaintiff is only required to pay the defendant’s costs. While a prevailing party is generally entitled to the recovery of costs in federal court without invoking Rule 68, some circuits limit costs recoverable to prevailing defendants in employment actions. Therefore, a Rule 68 offer of judgment may be employed as a useful tool to entitle a prevailing defendant to recover more litigation costs in these circuits.

Depending on what statute a plaintiff/employee sues under, there are two different results for a plaintiff’s accrual of fees when a defendant makes a Rule 68 offer that is more than the plaintiff receives at trial: (1) if suing under Title VII, Rule 68 does not permit a plaintiff to recover attorney’s fees; (2) if suing under the FLSA, ADA, or ADEA, Rule 68 does permit the plaintiff to recover attorney’s fees. Therefore, an offer of judgment is likely a better strategy for an employer in a Title VII case rather than an FLSA, ADA, or ADEA case. Additionally, there are some circumstances where the plaintiff’s fees may be limited by the court.

If the plaintiff prevails at trial after rejecting an offer of judgment, the defendant is still required to pay fees and costs up until the date the Rule 68 offer was made, even where the rejected offer is more than the plaintiff’s judgment. Rule 68 only requires a plaintiff to pay for the defendant’s costs accrued after the offer is made. The Rule is meant to encourage plaintiffs to settle, but for many plaintiffs the penalty of paying the defendant’s costs may not be overly burdensome. For that reason, if an employer is serious about making an offer of judgment, it is important to consider making it at the earliest stages of the case to limit the amount of pre-offer fees and costs for both parties.

Because the purpose of Rule 68 is to encourage settlement, the court’s process in awarding attorney fees takes into account the amount of the offer, when the offer was made, and whether it was reasonable to continue the litigation process after receiving the offer. Courts consider these factors in both Title VII and FLSA/ADA/ADEA cases.

Employers may be hesitant to make offers of judgment due to the stigma associated with such an offer. If the offer is accepted, the amount will be of public record. Employers may feel this will encourage others to make claims, which is clearly a valid concern. Fortunately, in federal court, unaccepted offers are not filed of record, but can still be used if a plaintiff is less successful at trial than the offer that was made. This benefit makes it worthwhile to at least consider the option.

Rule 68 Offers of Judgment Generally

“The purpose of Rule 68 is to encourage the settlement of litigation.” Delta Air Lines, Inc. v. August, 450 U.S. 346, 352, 101 S. Ct. 1146, 67 L. Ed. 2d 287, (1981). “Rule 68 provides an additional inducement to settle in those cases in which there is a strong probability that the plaintiff will obtain a judgment but the amount of recovery is uncertain.” Id.

“Because prevailing plaintiffs presumptively will obtain costs under Rule 54(d), Rule 68 imposes a special burden on the plaintiff to whom a formal settlement offer is made.” Id. If a plaintiff rejects a Rule 68 settlement offer and the final judgment award is less than the offer, the plaintiff will be required to pay the costs incurred to the defendant after the offer. Id.

A Rule 68 offer of judgment can be made only after a suit has been filed, but it must be made at least fourteen days before the date set for trial. Fed. R. Civ. P. 68(a); Lesley S. Bonney et. al., Rule 68: Awakening A Sleeping Giant, 65 Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 379, 383 (1997); see Clark v. Sims, 28 F.3d 420, 424 (holding that “a Rule 68 offer of judgment must be made after the legal action has been commenced. Offers of compromise made before suit is filed do not fall within the rule”). The opposing party will then have fourteen days after being served to send written notice accepting the offer. Fed. R. Civ. P. 68(a).

An unaccepted offer does not preclude a later offer of judgment. Evidence of an unaccepted offer is not admissible except in a proceeding to determine costs. Fed. R. Civ. P. 68(b). Rule 68 has no application to settlement offers made by the plaintiff. Delta Air Lines, 450 U.S. at 350.

Rule 68 offers of judgment should specifically mention whether attorney’s fees and costs are included in the amount offered. § 69:84. Offers of judgment, 2 Emp. Discrim. Coord. Analysis of Federal Law § 69:84. If a defendant is considering making an offer, it is best to do so early so as not to accrue as much in costs on either side. Although Rule 68 does not require any particular language in an offer, it does provide that the offer must also include the plaintiff’s costs incurred up to the date of the offer. Ian H. Fisher, Federal Rule 68, A Defendant's Subtle Weapon: Its Use and Pitfalls, 14 DePaul Bus. L.J. 89, 96 (2001).

A defendant may potentially block the plaintiff from obtaining his or her post-offer attorney’s fees through a successful Rule 68 offer. A. Jonathan Trafimow, Making Rule 68 Offers of Judgment in Employment Cases, Law360, New York (June 29, 2016) *Making-Rule-68-Offers-Of-Judgment-In-Employment-Cases.pdf (moritthock.com). If the defendant wins on merits, then Rule 68 does not apply and the defendant is not entitled to payment from the plaintiffs for its post-offer costs. Delta Air Lines v. August, 450 U.S. 346, 351–52 (1981) (more on this case below).

Whether the Governing Statute Includes Attorney’s Fees in Its Definition of “Costs”

A major issue with Rule 68 Offers of Judgment is that the drafters failed to define “costs.” Before making an offer, a defendant needs to consider whether a court will award the plaintiff its attorneys’ fees. Ian H. Fisher, Federal Rule 68, A Defendant's Subtle Weapon: Its Use and Pitfalls, 14 DePaul Bus. L.J. 89, 96 (2001). This can be particularly problematic in cases involving fee-shifting statutes.

In Marek v. Chesny, the Supreme Court determined the effect of Rule 68 on statutes involving fee-shifting of attorney fees. 473 U.S. 1, 8, 105 S. Ct. 3012, 87 L. Ed. 2d 1 (1985). The Court reasoned that “the most reasonable inference is that the term ‘costs’ in Rule 68 was intended to refer to all costs properly awardable under the relevant substantive statute or other authority.” Id. Further, the Court held that “all costs properly awardable in an action are to be considered within the scope of Rule 68 ‘costs.’” Id. Ultimately, the Court held that “absent congressional expressions to the contrary, where the underlying statute defines ‘costs’ to include attorney’s fees, we are satisfied such fees are to be included as costs for purposes of Rule 68.” Id. at 8–9.

Title VII’s Definition of Costs Implicitly Includes Attorney’s Fees

“Fee-shifting statutes in the employment discrimination context only provide for the prevailing plaintiff to obtain attorney’s fees.” A. Jonathan Trafimow, Making Rule 68 Offers of Judgment in Employment Cases, Law360, New York (June 29, 2016) at 2, *Making-Rule-68-Offers-Of-Judgment-In-Employment-Cases.pdf (moritthock.com). Title VII defines “costs” to include attorney’s fees by stating that “the court, in its discretion, may allow the prevailing party … a reasonable attorney’s fee (including expert fees) as part of the costs.” 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k) (emphasis added). Costs are interpreted to implicitly include attorney’s fees in a Title VII case.

Because Title VII’s definition of “costs” includes attorney fees, a plaintiff cannot recover attorney fees after a rejected Rule 68 offer of judgment, even when the plaintiff prevails at trial, but a plaintiff can still recover generated attorney fees up until the point of the offer. “[W]hen a plaintiff rejects a defendant’s Rule 68 offer, and then obtains less than that offer at trial, Rule 68 will not permit a prevailing defendant to obtain payment from the plaintiff for defendant’s attorney fees.” see, e.g., Tai Van Le v. University of Pennsylvania, 321 F.3d 403, 411 (3rd Cir. 2003) (holding that defendant is not entitled to attorney’s fees in in Title VII case when plaintiff received a less favorable judgment than defendant’s Rule 68 offer). Meaning, a defendant is only entitled to costs after a plaintiff rejects a Rule 68 offer and receives less at trial.

Title VII offers of judgment may include a specified amount of attorney’s fees or merely provide for a reasonable amount of fees to be determined by the court. § 69:84. Offers of judgment, 2 Emp. Discrim. Coord. Analysis of Federal Law § 69:84. “The troublesome questions concerning attorney’s fees in the context of offers of judgment may be avoided by defendants who are sincerely interested in settling the Title VII claim, without litigating, by routinely inserting a ‘reasonable attorney’s fees to be determined by the court’ provision in all offers of judgment, and by plaintiffs with similar interests accepting all reasonable offers of judgment in lieu of trial.” Id.

It is important to consider making an offer of judgment at the earliest opportunity to potentially limit each party’s costs and attorney’s fees. If the defendant’s offer is rejected and the plaintiff’s judgment is less than the offer, the defendant is only required to pay costs and attorney’s fees generated before the offer was made.

Although attorney fees are implicitly included as costs under Title VII, a defendant should specify that its offer includes costs and attorney fees.

Two cases for consideration:

In Sanchez v. Prudential Pizza, Inc., 709 F.3d 689 (10th Cir. 1999),an employer’s offer of judgment, which specified that it applied to “all of Plaintiff’s claims for relief” in her Title VII suit, did not include the employee’s claim for attorney fees and costs. Id. at 690. Thus, the employee’s award of attorney fees and costs was warranted, even though the employee sought attorney fees in her complaint. Id. at 694. The Seventh Circuit noted that “Rule 68(a) requires the offer to include “specified terms.” Id. at 692. The court reasoned that “an ambiguous offer puts the plaintiff in a very difficult situation and would allow the offering defendant to exploit the ambiguity in a way that has the flavor of ‘heads I win, tails you lose.’” Id. at 693–94. For instance:

[i]f the plaintiff accepts the ambiguous offer, the defendant can argue that costs and fees were included. If the plaintiff rejects the offer and later wins a modest judgment, the defendant can then argue that costs and fees were not included, so that the rejected offer was more favorable than the ultimate judgment and that the plaintiff’s recovery of costs and fees should be limited according.

Id. at 694 (emphasis in original). The Tenth Circuit held that:

‘[i]f an offer recites that costs are included or specifies an amount for costs, and the plaintiff accepts the offer, the judgment will necessarily include costs; if the offer does not state costs are included and an amount for costs is not specified, the court will be obliged by the terms of the Rule to include in its judgment an additional amount which in its discretion it determines to be sufficient to cover the costs.’

Id. (quoting Marek, 473 U.S. at 6). Holding: if terms of Rule 68 offer are ambiguous, it will be construed against the defendant-offeror.

In Delta Air Lines, Inc. v. August, 450 U.S. 346, 101 S. Ct. 1146, 67 L. Ed. 2d 287 (1981), the plaintiff, a flight attendant, filed a complaint against the defendant, Delta Air Lines, alleging that she had been discharged because of her race in violation of Title VII. Id. at 348. She sought reinstatement, about $20,000 in backpay, attorney’s fees, and costs. Id. The defendant made a formal offer of judgment to the plaintiff in the amount of $450. Id. The plaintiff did not accept the offer and at trial the plaintiff lost. Id. at 348–49. The district court entered judgment in favor of the defendant and directed that each party bear its own costs. Id. at 349.However, the defendant then moved for modification of judgment, contending that under Rule 68 the plaintiff is required to pay the costs incurred by the defendant after an offer of judgment has been refused. Id. The court denied the motion on the ground that the $450 offer was not a good-faith attempt to settle the case. Id. The appellate court affirmed, holding that Rule 68 only applies if the defendant’s settlement offer was sufficient “to justify serious consideration by the plaintiff.” Id.

The issue in this case was whether the words “judgment finally obtained by the offeree” as used in Rule 68 should be interpreted to include “a judgment against the offeree as well as a judgment in favor of the offeree. Id. at 347–48 (emphasis in original).

The Court reasoned that the plain language of Rule 68 states that the rule applies when the defendant offers to have “‘judgment … taken against him.’” Id. at 351. The Court noted that because “the Rule obviously contemplates that a ‘judgment taken’ against a defendant is one favorable to the plaintiff, it follows that a judgment ‘obtained’ by the plaintiff is also a favorable one.” Id. Thus, the Court found that the Rulemakes clear that “it applies only to offers made by the defendant and only to judgments obtained by the plaintiff,” so the Rule was inapplicable to the plaintiff’s case.

Ultimately, the Supreme Court held that “the Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 68—which provides that if a plaintiff rejects a defendant's formal settlement offer ‘to allow judgment to be taken against him,’ and if ‘the judgment finally obtained by the offeree is not more favorable than the offer,’ the plaintiff ‘must pay the costs incurred after the making of the offer’—does not apply to a case in which judgment is entered against the plaintiff-offeree and in favor of the defendant-offeror.” Id. at 346. Holding: a defendant is not entitled to costs in Title VII case where plaintiff rejects a Rule 68 offer and subsequently loses at trial.

FLSA, ADA, and ADEA’s Definition of Costs Does Not Include Attorney Fees

The FLSA provides for a mandatory award of attorney’s fees and costs to an employee who prevails on his or her claim. 29 U.S.C. § 216(b). The statute does not define costs as including attorney’s fees: “The court in such action shall, in addition to any judgment awarded to the plaintiff or plaintiffs, allow a reasonable attorney’s fee to be paid by the defendant, and costs of the action.” 29 U.S.C. § 216(b) (emphasis added). The ADA and ADEA also do not include attorney’s fees as part of costs. 42 U.S.C. § 12205 (ADA); 29 U.S.C. § 626 (ADEA – incorporating fee-shifting provisions from FLSA).

If no Rule 68 offer is made, a prevailing plaintiff will recover both attorney’s fees and costs, whether the judgment is less than or higher than a previous settlement offer. On the other hand, if a Rule 68 offer is made by the defendant and the judgment for the plaintiff is less than the offer, the plaintiff will still recover fees to the date of the offer and the defendant will only recover costs incurred after the date of the offer.

Additionally, it appears that courts will take a Rule 68 offer into account when determining the amount of fees a plaintiff may recover. Dalal v. Alliant Techsystems, Inc., 182 F.3d 757, 761 (10th Cir. 1999). In Dalal, an ADEA case, the district court awarded fees generated before the Rule 68 offer, but only awarded half of the fees accrued after the offer. Id. The Rule 68 offer was $150,000 and the judgment at trial for the plaintiff was only $36,075. Id. The district court also lowered the plaintiff’s fee amount based on the “limited success” of his Title VII claim. Id. The Tenth Circuit held that the district court’s determination of fees was in its discretion, noting that “‘there is no precise rule or formula for making such determinations.’” Id. at 763 (quoting Berry v. Stevinson Chevrolet, 74 F.3d 980, 990 (10th Cir. 1996)).

In deciding an attorney fee award, Courts consider various factors. In Haworth v. State of Nev., 56 F.3d 1048 (9th Cir. 1995), state employees sued the state under FLSA. The state’s offer of judgment was more than the final judgment for the employees. Id. at 1050. The district court awarded the employees costs and attorney fees. Id. The Ninth Circuit Court held that the state’s offer of judgment did not bar the award of the attorney fees under FLSA, even though the final judgment was less than the Rule 68 offer. Id. at 1052. The Court further held that in determining what amount of attorney’s fees are reasonable in an FLSA action with an offer of judgment, a court must consider the following: the amount of the offer, the stage of litigation at which the offer was made, what services were rendered thereafter, the amount obtained by the judgment, and whether it was reasonable to continue litigating the case after the offer was made. Id. at 1052–53. The Ninth Circuit vacated the district court’s award of costs to the plaintiff because they were not entitled to any costs incurred after they rejected the Rule 68 offer. Id.

Conclusion

While an offer of judgment will not make sense in every employment case, it is worthwhile to consider, especially in Title VII cases. However, its effectiveness diminishes as a case progresses, so it is important to consider an offer of judgment very early in the litigation.

Articles:

Lesley S. Bonney et. al., Rule 68: Awakening A Sleeping Giant, 65 Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 379, 383 (1997).

Ian H. Fisher, Federal Rule 68, A Defendant's Subtle Weapon: Its Use and Pitfalls, 14 DePaul Bus. L.J. 89, 96 (2001).

Kevin C. Johnson, Rule 68 and the High Cost of Litigation: The Best Defense Weapon of Which You've Never Heard and Its Missed Opportunity to Promote Settlement, 10 Charleston L. Rev. 475 (2016).

A. Jonathan Trafimow, Making Rule 68 Offers of Judgment in Employment Cases, Law360, New York (June 29, 2016) at 2, *Making-Rule-68-Offers-Of-Judgment-In-Employment-Cases.pdf (moritthock.com).

§ 69:84. Offers of judgment, 2 Emp. Discrim. Coord. Analysis of Federal Law § 69:84.

Malinda Matlock is a Partner with Rhodes Hieronymus in Oklahoma. She practices in the areas of Professional Liability (Medical, Legal, A&E, E&O, D&O), Employment Litigation, Sexual Misconduct, Premise Liability, Transportation, Bad Faith Insurance Claims, and Coverage Disputes.

Denelda L. Richardson is a partner in Rhodes Hieronymus whose practice focuses on litigation and appellate practice, with an emphasis on claims of employment discrimination under both federal and state law.

Malinda and Denelda would like to give special thanks to Meredith Tan, Law Student, for her enthusiastic assistance in researching how courts across the country have applied Rule 68 in the employment context. |

|

|

Buckle Up for New Roads Ahead: Product Liability and Autonomous Vehicles

Adam Fogarty, M.S., P.E.

SEA, Ltd., Rolling Meadows

As technology marches forward, many of the tasks that people were once burdened with are being addressed by sensors, circuit boards, and processors. The rate of information transfer from Point A to Point B is ever accelerating, allowing for incredible paradigm shifts to occur across several industries.

One such shift is the approach towards the goal of self-driving vehicles, which has garnered much attention recently due to many hardware and software advancements that have allowed this objective to become much more realizable. One such advancement is the implementation of Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS), which perform tasks such as adaptive cruise control, lane keep assist, forward collision warning and blind spot monitoring.

Since a variety of sensors and processors are used to control ADAS systems, manufacturers are able to apply similar hardware and object recognition techniques towards the target of self-driving. Although there are differences in the ways each manufacturer constructs and implements their ADAS systems, there are certain sensors and devices that are commonly used. For a vehicle to drive itself, it must first be able to detect the world around it. To do this, devices such as ultrasonic sensors, RADARs, LIDARs, and cameras, are being used in unique ways.

Ultrasonic sensors rely on high-frequency sound waves that are sent and received by each sensor. Because sound waves are the method of detection, the color of a detected object is irrelevant, and the absence of light is not a hindrance. Such sensors are short range and can be small and lightweight. Therefore, they are commonly built into the front and rear fenders of vehicles for close-range object detection. This can allow for park-assist features that warn drivers when they are too close to large objects, such as a nearby car or wall.

RADAR sensors use electro-magnetic (EMF) waves for object detection. Both short-range and long-range RADAR systems can be used with effective ranges beyond 500 feet, unlike the shorter ranges of ultrasonic sensors. However, forward-facing RADAR units are similar in that they can be implemented on the front fender of a vehicle. Their longer range of detection can allow for features such as adaptive cruise control, forward collision warning, and emergency braking.

LIDAR systems use a rotating, pulsed laser for object detection. Since a laser is used as the detection method, LIDAR has a long effective range, and can operate in the absence of daylight. LIDAR systems can measure the distance of objects with precision and accuracy and can produce a high-resolution image of the environment surrounding the unit. However, since the laser needs to rotate and sweep across the landscape, time is required for a complete image to form. Traditionally, it has been difficult to equip vehicles with LIDAR systems due to their size and cost. However, newer generations of LIDAR systems reduce the cost, size, and latency of information collection.

Cameras are devices seen on many consumer products across the globe. Due to their popularity, the acceleration of camera technology has been incredibly fast. They are smaller, cheaper, and higher resolution than ever before. Cameras can be implemented on several different parts of a vehicle, assuming they have an unobstructed view. With several cameras facing different directions, a full 360-degree vision envelope can allow a vehicle system to see in all directions at all times. Additionally, cameras can utilize different vision spectrums, such as infrared for more robust nighttime operation. However, one challenge lies in the fact that cameras do not measure distance from the objects observed.

By using combinations of ultrasonic sensors, RADARs, LIDARs, and cameras (among other components), vehicles can detect much of their surroundings in real time. With a variety of object detection methods, the strengths of one system can make up for the weaknesses of another. For instance, since some cameras rely on light to observe an object, nighttime driving or fog may become a challenge for that camera system. Despite this, if a different sensor (such as a RADAR) is facing the same direction at the same time, the RADAR may be more effective than the camera.

Each sensor collects data that must be processed and analyzed in order for a vehicle to recognize the environment. For instance, a camera records images in the form of a matrix of pixels, each of which carries a value that corresponds with a specific color. Therefore, rather than seeing objects directly, software systems are instead given long arrays of values. One technique used to decipher and analyze these arrays is known as a neural network.

Neural networks are a software strategy inspired by the workings of the human brain. Rather than being instructed directly, they are instead trained using immense amounts of data. For this training to take place, an “answer sheet” must be created. Since humans are naturally able to recognize objects, they are used to create each answer sheet. For instance, a person can be shown a group of images, then they can select which images contain pictures of objects, such as cars, bicycles, road signs, lane lines, etc.

Once an answer sheet is created, neural network training can take place. First, a neural network can begin as a blank page attempt to answer a question. The structure of the network is a series of nodes that are connected to each other, similar to the network of neurons in a human brain. Once the network is shown the answer to the question it is seeking to answer, the network pathways that relate to the correct answer are strengthened. If this process is repeated, the network will become more effective at answering the type of question it was trained to answer.

If a neural network is being trained to recognize objects for the purpose of driving a vehicle, it is important to remember that the real world is full of unique circumstances which may fall outside of the trained neural network. No two situations are the same, and random encounters are not uncommon. Therefore, when training a neural network for self-driving, answers must be provided that are as diverse as the real world. For example, if a network is shown nothing but straight, empty roadways, it will only see the world as a series of straight, empty roads. Instead, diverse, realistic data incorporating things like twists, turns, hills, angles, trucks, cars, bicycles, pedestrians, etc. should be included.

Once a network can recognize objects, it is critical to assign distance values to them. If a system has sensors, such as LIDAR and RADAR, these can be used to measure objects that are recognized. However, it is possible for a system of cameras to calculate, rather than measure distances to recognized objects.

One method for this is known as binocular vision. In sum, multiple camera perspectives of the same object can be compared to each other to calculate its distance. This is how humans determine the distances of objects that they see, as they have two eyes viewing objects from unique perspectives.

Another distance determination method relies on a single camera perspective, but requires that objects move in order for their distance to be approximated. The same strategy is used by some animals to perceive the distance of predators in nature.

Once a vehicle can recognize its surroundings, it must also recognize where it is currently located. A Global Positioning System (GPS) can directly measure the location of a vehicle. Additionally, this location can be traced over time to create known pathways of where vehicles may travel. Therefore, previous driver pathways can be used to predict where vehicles should be traveling.

Additionally, if a particular neighborhood or roadway has been well documented by the GPS tracking of other vehicles (or LIDAR equipped test vehicles), the area may be an acceptable area of travel for a self-driving car. Therefore, GPS can be used to restrict areas of autonomous driving to only certain areas. This technique is known as “Geofencing.”

No system is impervious to disturbance, and the hazards of driving are broad and diverse. One type of disturbance comes in the form of sensor blockage. Whether it be snow, mud, or even large insects, it is possible for RADARs, LIDARs, or cameras to get blocked momentarily. Therefore, it is critical for an autonomous vehicle to be well equipped with a diverse array of overlapping sensors, so one sensor can make up for another in times of need. More robust sensor suites with stronger overlap can eventually circumvent the challenge of sensor blockage.

In any vehicle accident, it is important to understand if a vehicle malfunction contributed to or caused the accident. Similarly, in accidents involving ADAS equipped vehicles, an evaluation of the many systems, sensors, and components will be important in understanding crash causation. Therefore, it is beneficial if a vehicle records electronic data from its sensors and specifies whether or not the ADAS technology was in control of the vehicle at the time of the crash.

Full self-driving technology will not be implemented immediately, so it is important to remember that such features are being added piece by piece as ADAS, such as adaptive cruise control, blind spot monitoring, forward collision warning, active lane keep (a technique used to keep vehicles from drifting out of their lane), and self-driving operation only when the driver is engaged and paying attention. Therefore, drivers can become more familiar with self-driving techniques as they evolve.

However, it cannot be assumed that pedestrians or other drivers are familiar with the specific features of a given vehicle. With this in mind, it is difficult to anticipate how pedestrians and other drivers will react to the actions of an autonomous vehicle. For instance, if an autonomous vehicle and a human-operated vehicle are attempting to park in the same spot, there may be miscommunications that occur as one vehicle tries to anticipate the decisions of the other.

Regardless, many companies are chasing this goal of self-driving, which will increasingly be influenced by artificial intelligence. With multiple sensor redundancy and ever-improving processing times, autonomous vehicles have immense potential, and have already demonstrated themselves to be fully capable of safe operations under certain conditions. As more vehicle automation takes place, more data can be fed into neural networks, creating ever-improving vehicle systems that may ultimately surpass the capabilities of human-operated vehicles. The legal, ethical, and technical challenges will be pervasive, but certainly there are many safety advantages to consider as autonomous vehicles become more prevalent in the future. - (SEA Ltd.) |

Ransomware: Real Life Battle Bots

by: Marci De Vries, Fraudsniffr

My husband and I watch a lot of robot movies, and we always start laughing when two giant robots stand up and start punching each other with their giant metal fists. It’s funny because a real robot war would look like two server boxes getting really hot. Maybe toss in melted router for added dramatic effect.

In real life, ransomware is a $3 billion industry, perpetrated by infinite testing and vulnerability detection. Because American company firewalls and intrusion detection systems are typically handled by software that does not detect macro trends, a bad actor can test and locate vulnerabilities without ever alerting a human. The bad actor simply uses an array of VPNs to sidestep the rudimentary pattern analysis included in most server security protocol while they look for paths into the data.

After an intrusion point is located, the bad actor can inject code that does not deploy as a ransomware attack for months. This quiet code completes a variety of tasks – first it copies data and delivers that data to the bad actor, then it tags data for deletion during the future ransomware attack. The code also flows into any machine that sends data to the affected device, and out to any device where the machine sends data. In this way the ransomware affects not only the machine that had the vulnerability, but also to all the data on all the devices connected to that machine. It is an elegant way to bypass any firewall system to infect an entire network, even reaching out to the laptops and flash drives of remote workers. Most ransomware code also has AI included to identify the most critical data, based on usage, frequency, and type. The bad actor assesses the relative value of the data and compares it against a sophisticated financial analysis of the victim to calculate the ransom demand.

This quiet ransomware code does its work for six months or more, just long enough to outlast a standard backup/restore process – most companies keep full backups for six months, and then only periodic (and not very useful) backups from earlier dates. This long quiet period makes it impossible for a company to restore their systems from any existing useful backups. Furthermore, if a company tries to restore from a backup that includes ransomware code, often the ransomware attack will become even more aggressive and delete additional data from the affected device(s).

Companies in the middle of an active ransomware attack are often incredibly surprised at the customer service and professionalism exhibited by the bad actor who has made the ransom demand. If the company representatives are willing to pay the ransom, the process of retrieving data is very straightforward. At the end of a successful ransomware transaction, the data is fully restored and a company can resume operations as if the attack had not happened. However, for companies that want to fight the ransomware actors, the data can be returned damaged, or not returned at all.

The maddening part of ransomware attacks is that they are nearly random. Ransomware attacks that haven’t made the national news include my son’s school district, a local hospital system, a cardiac surgery unit within a medical system, a mid-sized document imaging company, and a municipality’s technical infrastructure. It could be as random as this: ransomware bots start with a vulnerable device, and then walk through not only a company’s infrastructure, but also the company’s hosting provider. Once a ransomware bot infects a hosting provider, the bots might even spread to the other companies hosted in the same facility. In reality, at this point there does not seem to be a pattern to the selection of ransomware victims.

So how can a risk manager address the ransomware threat? According to Swadesh Guchhait, president of Alliance Infosystems, a Baltimore-based IT company that specializes in network security, the biggest mistake enterprises make is focusing on the leading edge of their network security – while a robust firewall is important, it will not provide systemwide protection.

Companies interested in slowing down or stopping a ransomware attack need to segment their network, which would prevent a bad actor from moving horizontally through a network once it is behind the firewall. Segmenting means putting the HVAC computer system on a separate network from the production network, and segmenting Wi-Fi from the main data network. Network design and hygiene is the most effective way to limit the extent of a ransomware attack.

Guchhait also indicates that end point security (computers used by humans on a network) is the primary intrusion point for ransomware. Training employees device usage is important, especially as bad actors produce increasingly salacious content to entice clicks.

There are some standard practices to engage in as well, it is important to install network protection that scans for active and dormant viruses, with the understanding that this is a best practice, not a foolproof protection plan.

It’s a dangerous new war we’re fighting. The attacks are civilian companies, and the people at the front line are you and me. Stay safe out there, and don’t click on anything you don’t recognize. |

Human Fatigue Risk Management in Workplace Settings: Implications for Litigation

Chason J. Coelho, Ph.D., CSP, CFI

Exponent | Senior Managing Scientist | Human Factors

15375 SE 30th Place, Suite 250, Bellevue, WA 98007

[email protected]

Sunil D. Lakhiani, Ph.D., P.E., CSP

Exponent | Managing Engineer | Human Factors

4580 Weaver Parkway, Suite 100, Warrenville, Illinois 60555

[email protected]

Delmar R. "Trey" Morrison, III, Ph.D., P.E., CCPSC, FAIChE, CFEI

Exponent | Principal Engineer | Thermal Sciences

4580 Weaver Parkway, Suite 100, Warrenville, Illinois 60555

[email protected]

Introduction

Human fatigue is a peculiar issue for workplace safety and risk management. Scientific and industry literature has linked fatigue to adverse health and performance effects, but organizations, individuals, and regulators alike have struggled to manage fatigue risks. Here we describe several challenges of fatigue risk management and review a new approach being adopted: the fatigue risk management system (FRMS). We also point out that as the FRMS sees more widespread adoption, companies are starting to face a new fatigue-related challenge – legal liability related to fatigue management.

A brief review of fatigue is given below. An example of a high-profile industrial incident involving fatigue follows, with relevant statistics, some specific challenges of fatigue management, historical context, and implications for litigation noted thereafter.

Human Fatigue

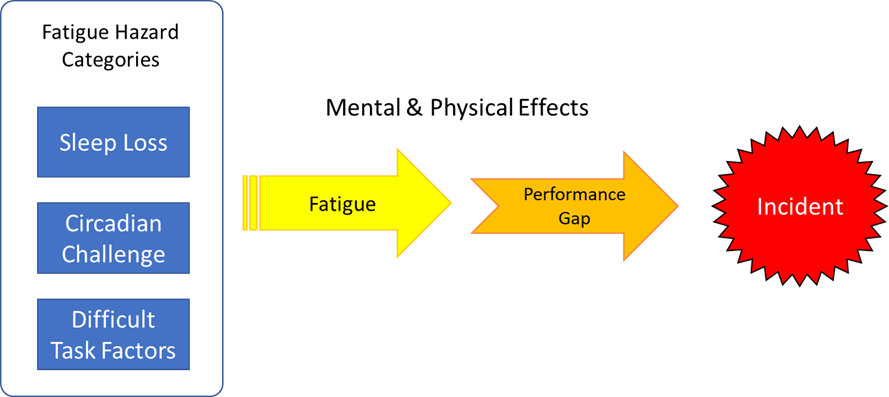

Fatigue is a state of reduced mental or physical performance capability that results from sleep loss, circadian challenge, difficult task factors, or a combination thereof [1, 2]. Figure 1 illustrates that mental and physical fatigue serve as a link between fatigue hazards (e.g., long commutes, shiftwork, etc.) and accidents.

|

Figure 1. Fatigue-related incident event chain – adapted from Coelho et al. (2019)

A high-profile incident involving fatigue entailed an explosion and subsequent fire at the BP Texas City Refinery in 2005; fifteen people perished, and 180 were injured [3]. An investigation by the U.S. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board found that the board operator had worked 12-hour shifts for at least 29 consecutive days, and the report suggested that fatigue-related human error contributed to the incident [3]. The company had neither a corporate nor a site-specific fatigue-prevention policy at that time, and its contract with the labor union specified a minimum number of work hours each week but not a maximum [3]. This incident directly led to significant fines, settlements, business interruption, and corporate governance changes for BP. Fatigue played a part.

Research has statistically linked workplace fatigue and workplace fatalities and injuries. For example, one study reported that of the approximate 360,000 fatalities and 960,000 injuries that occur in workplaces worldwide each year, about 13% can be attributed to fatigue in some way [4]. It also appears that almost one quarter of the U.S. adult population experiences significant sleep problems [4]. Reduced sleep and longer work hours are associated with greater injury risk [5], and nighttime workers are almost three times more likely to be injured than daytime workers [6]. Jobs that require overtime are also associated with a 61% higher injury rate compared to jobs without overtime [7].

Other research suggests that these statistics are linked to poor human performance. A meta-analysis showed that fatigue can make people perform worse than 90% of rested people on various tasks [8]. Fatigue-related performance impairments can include slower reaction-time, divided-attention, and poor memory recall, which are similar to the performance deficits resulting from alcohol intoxication [9]. Fatigue can also impair judgment, planning, learning, and situation awareness [10]. It is perhaps unsurprising, then, that industrial organizations are becoming more and more interested in developing programs for managing fatigue.

Managing Fatigue

Managing fatigue has proven challenging for several reasons. Fatigue is quite common [11], and individuals can struggle to accurately assess their own fatigue levels [12]. There are many potential work-based fatigue hazards, including, but certainly not limited to:

- Long shifts

- Stress

- Overtime

- Work-related worry

- Monotonous tasks

- Poor ergonomics

- Performance milestones

Indeed, the sheer number of fatigue hazards may make it difficult for organizations with little or no experience in fatigue management to properly identify, mitigate, and control the risk associated with all the hazards. Another challenge that makes fatigue a somewhat unique workplace hazard is that fatigue-inducing activities and demands may arise outside the workplace. Employees can arrive at the workplace already fatigued from dealing with commutes, children, sleep disorders, or other daily life issues.

Industry- and site-specific facility and operational features can pose unique fatigue risks. For example, some industries such as oil and gas extraction can require remote operations, and it can be common to see schedules with runs of 14 contiguous days entailing 12-hour shifts. Attempts to hold organizations responsible for evaluating and controlling industry-, facility- and operations-specific risks may become more frequent as scientific and industry literature on fatigue management continues to grow.

Traditional Approach to Fatigue Management

Individuals, companies, and regulators have traditionally relied on prescriptive methods, such as imposing on-duty limitations [13]. Two common prescriptions are hours-of-service restrictions and minimum rest breaks. Prescriptions can be helpful in limiting some fatigue risk; however, stakeholders across industries are realizing that theses prescriptions do not commonly or specifically limit worker exposure to fatigue risks associated with typical human sleep patterns, duty cycles, and non-work-related time [13]. To address these sometimes unique and variable risks, organizations and regulators have been turning to more formal fatigue risk management practices.

Fatigue Risk Management System (FRMS)

The FRMS is a risk-based approach being adopted in many industries to monitor and manage fatigue-related safety risks. These industries include, but are not limited to, aviation, commercial driving, rail, nuclear, and oil and gas. The FRMS takes a traditional safety management system (SMS) approach, which includes four basic components: policy, risk management (i.e., hazard identification, risk assessment, and risk mitigation), assurance (e.g., auditing), and promotion (e.g., internal communication and training).

Whereas an SMS addresses many workplace hazards, an FRMS specifically addresses fatigue-related hazards. It then relies on scientific principles and operational experience to help personnel mitigate fatigue risk and work with proper alertness [1]. Different FRMS versions exist across industries, but most versions entail the following elements:

- Introductory materials that convey purpose, objectives, scope, and accountability;

- Policy statements that convey organizational commitment;

- Scientific information on sleep, fatigue, and fatigue countermeasures;

- Fatigue risk-assessment (FRA) and countermeasure procedures and guidance;

- Assurance and continuous-improvement procedures and guidance;

- Fatigue awareness and training; and

- Implementation and communication plans.

Recent research has provided evidence that such fatigue management initiatives may be helping [14]. For example, data from 70 companies across a range of industries were analyzed to assess the relations between self-reported fleet safety management practices and motor vehicle collision and injury metrics. Results indicated that the presence and practice of fatigue risk management and mitigation policies and practices predicted lower injuries per million miles traveled [14].

A Practical Approach

We have been helping clients meet fatigue management challenges by providing practical guidance on (a) developing an FRMS, (b) efficiently integrating it with the existing company SMS to save on effort, and (c) assessing whether fatigue contributed to an incident within its incident investigation and root cause analysis protocols.

We have specifically focused on a core FRMS component – the fatigue risk assessment (FRA). Respecting that it helps to have relatable and practical ways to conduct FRAs, one type of FRA for which we have advocated is strategically designed to mirror an existing risk assessment process that is already well known to many safety professionals. This FRA process is designed to (a) identify situations where fatigue may pose hazards, (b) assess the risks presented by those fatigue hazards, (c) note existing countermeasures, and (d) decide whether those countermeasures are adequate or whether additional ones are required to mitigate or control the fatigue risk. The FRA process therefore offers a systematic method for understanding the precursors to human error in incident scenarios. Such a process can be used by organizations to start addressing fatigue and, in turn, potentially reducing the liability of not addressing it. This approach can also be applied to evaluate factors related to human fatigue that may have contributed to an incident.

As alluded to above, another component of our fatigue-related work has focused on supporting clients who are alleged to have not adequately addressed fatigue through management oversight. Such allegations are typically connected to incidents involving serious injury or fatality. Claims are likely to be that the behavior of an employee was a proximate cause of the incident, and that the behavior was driven by fatigue, which, in turn, resulted from poor organizational oversight of the employee.

One approach to this type of situation is to first review applicable company standards, policies, and other administrative controls (SPAC), such as those directly addressing journey and fatigue risk management. Also important to assess are relevant regulatory and industry consensus standards. Some industries have regulatory standards that clearly apply, such as the (a) Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) regulations in commercial and general aviation, (b) Federal Motor Carriers Safety Administration (FMCSA) regulations in commercial trucking, and (c) Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) regulations in gas control room operations. In some cases, however, no such regulatory oversight is applicable, and instead voluntary consensus standards should be considered as references; context is especially important here, and care should be taken to understand that these consensus standards can exist in varying stages of maturity and visibility to industry stakeholders. In turn, these points have implications for what can be expected of a reasonable company given the constraints and common patterns of practice in its industry.

Closing Remarks

Whether and how these issues are brought to bear inevitably depends on the specifics of the case at hand. One thing is relatively certain, however: questions will not only be asked about whether regulatory prescriptions were satisfied but also about whether and how the conduct of the company accorded with literature on the emerging reference for fatigue risk management in workplace settings – the FRMS. Moreover, it is reasonable to expect the frequency of these sorts of questions to increase as this literature continues to develop.

References

[1] “Fatigue-Risk Management Systems (FRMS): Implementation Guide for Operators,” ICAO / IATA / IFALPA, 1st Ed., 2011.

[2] American Petroleum Institute, “API Recommended Practice 755. Fatigue Risk Management Systems for Personnel in the Refining and Petrochemical Industries.” Report No. 2005-04-I-TX, API, Houston, Tex. (2010).

[3] U.S. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board. “Investigation Report, Refinery Explosion and Fire,” CSB, 2007.

[4] Uehli, K., et al., “Sleep Problems and Work Injuries: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.” Sleep Medicine Reviews, 18(1), pp. 61-73 (2014).

[5] Lombardi, D.A., “Weekly Working Hours, and Risk of Work-related Injury: US National Health Interview Survey (2004–2008).” Chronobiology International, 27(5), pp. 1013-1030 (2010).

[6] Swaen, G.M.H., et al., “Fatigue as a Risk Factor for Being Injured in an Occupational Accident: Results from the Maastricht Cohort Study.” Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 60 Suppl 1, pp. i88–i92 (2003).

[7] Dembe, A.E., et al., “The Impact of Overtime and Long Work Hours on Occupational Injuries and Illnesses: New Evidence from the United States. Occupational and Environmental Medicine,” 62(9), pp. 588-597 (2005).

[8] Pilcher, J.J. and A.I. Huffcutt, “Effects of Sleep Deprivation on Performance: A Meta-analysis.” Sleep, 19(4), pp. 318-326 (1996).

[9] Roehrs, T., et al., “Ethanol and Sleep Loss: A ‘Dose’ Comparison of Impairing Effects.” Sleep, 26(8), pp. 981-985 (2003).

[10] Wickens, C.D., “An Introduction to Human Factors Engineering.” Pearson Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, N.J. (1998).

[11] Bonnet, M.H. and D.L. Arand, “We Are Chronically Sleep Deprived,” Sleep, 18, pp. 908-911 (1995).

[12] Lerman, S.E., et al., “Fatigue Risk Management in the Workplace.” Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 54(2), pp. 231-258 (2012).

[13] Gander, P., et al., “Fatigue Risk Management: Organizational Factors at the Regulatory and Industry/Company Level,” Accident Analysis & Prevention, 43(2), pp. 573-590 (2011).

[14] Vivoda, J.M., Pratt, S.G., and Gilles, S.J. “The relationships among roadway safety management practices, collision rates, and injury rates within company fleets,” Safety Science, 120, pp. 589-602. |

|

Issues That Can Cause Problem Bars - A View from the Eye of a Hurricane

John A. Cocklin- Exigent Group Limited: Forensic Consulting Division

Dram Shop, Alcoholic Beverage Regulation, and Police Practices Expert

I am writing this article from the imposed quarantine of my home office. We are witnessing the almost overnight shutdown of the United States’ hospitality industry that in 2019 employed an estimated 16.78 million persons[1]. Not since the passage of the 18th Amendment and the subsequent beginning of Prohibition on January 17th, 1920, has this industry segment undergone such a seismic shift.

Today we are all waiting for the National emergency created by the virus pandemic COVID-19 to run its course and allow for the re-start of this massive economic engine. It is in this context (that of being in the eye of an economic hurricane) that I consider issues that will, as it has in the past, affect the on-premise retail alcohol industry as it re-starts and seeks to re-gain profitability.

HISTORY - Alcohol is a highly regulated industry, governed primarily by the individual states through the authority granted to them by ratification of the 21st Amendment of the US Constitution on December 5, 1933. In the ensuing eighty-six years, the United States Supreme Court has ruled on various alcohol related issues created by the inconsistencies between the Constitution’s commerce clause and the states’ rights to regulate alcoholic beverage manufacture, distribution, sale and consumption. The Court has generally upheld the states’ rights to promulgate laws and regulations that promote the health, safety and welfare of the public.

While each of the fifty states (and the District of Columbia) have established their own alcohol regulatory scheme, there are three general commonalties that tend to transcend state borders. They are:

- Alcohol is a prohibited product, unless manufactured, distributed and sold by either state entities or private businesses regulated and licensed by the state. As a businessman operating within this regulated industry, he/she must abide by the laws and regulations under pain of criminal prosecution, and/or the administrative suspension or revocation of his/her license to operate. This means they must seek to maximize profits while operating within the confines of the regulatory scheme. The license holder (licensee) becomes BOTH an owner of a for profit business and a gatekeeper who enforces the laws and regulations. The two most universal restrictions are:

- The retail sale of alcoholic beverages to a person under the legal age (PULA) to purchase is prohibited. Such a sale could result in criminal charges, the suspension or revocation of the license to operate and, where injuries or damages result, civil liability.

- The retail sale of alcoholic beverages is prohibited to a person, who at the time of service, exhibited signs of intoxication.[2]

The inattention by the licensee, their management and staff to these Gatekeeping responsibilities can create a problem bar – a licensed retail on-premise alcohol establishment whose business practices fall below the standards established by the regulatory scheme and thereby create dangerous conditions adversely affecting the health, safety and welfare of the public.

Underage Patrons (PULA) – I was once told by a Prosecutor “that underage drinkers are like cockroaches. If you see one or two, you probably have a hundred patronizing your business.”

All retail Licensees are required to take reasonable measures to detect PULAs and prevent them from purchasing, possessing or consuming alcoholic beverages on the licensed premise. This gatekeeping function requires house policies and procedures to ensure staff diligence and consistency in the identification of potential underage patrons, the request to produce acceptable identification and the careful examination of the identification and patron.

This gatekeeping function is not just for the staff assigned to the door. All the staff, from the licensee, the management, the bartenders, the service staff and the security are responsible for the implementation of PULA detection procedures. It is okay for a youthful patron to be “carded” by the staff multiple times during a visit – in fact, such diligence is advisable. A well-trained staff member can place the patron at ease while making the point that the establishment does not tolerate nor welcome PULAs. When effectively implemented, the establishment quickly develops the reputation that it is not the place to go and attempt to purchase alcohol if you are underage.

Usually, state requirements limit acceptable identification to:

- A currently valid state driver’s license, or in some states a valid state identification card

- A valid passport

- A military identification

Any other type of identification is unacceptable.

When checking identification, the staff should examine:[3]

- Date of birth

- Date of expiration

- The embedded government seal / hologram

- Photo – (is it the person you are examining)

- Signature

- Issuing Authority

The staff should always request that the guest remove the identification from a wallet. Well run establishments encourage their staff to question the patron about the information on the identification. Questions such as: “I see you live in Podunk. My best friend is from Podunk. What high school did you attend? When did you graduate?” can frequently trip up a nervous person pretending to be older than they are. Finally, if your state recommends an age verification scanner, swipe the card through the device. If the establishment has a state provided gaming or lottery terminal with a gaming/lottery age verification feature, use it for alcohol age verification. This establishes a reasonable practice using state supplied equipment.

The absolute policy must be: When in doubt, don’t allow the person to purchase or consume alcohol on the licensed premise.

Since the mid-2000s, criminal elements, often from Eastern Asia, produce and sell almost undetectable counterfeit driver’s licenses via the internet, the dark web and other sources. These sites are well known on almost any college campus in the United States. The counterfeit licenses will contain the actual photograph of the holder and are almost impossible to detect as bogus. The counterfeit license will scan and to the casual observer look genuine. If, however, the counterfeit license is examined by law enforcement, and compared to the information contained in Department of Motor Vehicle databases, the query will result in a “no record found” since the date of birth has been altered. Generally, an alcohol establishment does not have access to restricted government databases, so the establishment must rely on the reasonable diligence of its staff to verify.

Over Service of Patrons – In most states it is prohibited by the regulatory scheme for an establishment to sell or serve alcohol to any patron who, at the time of the sale or service, demonstrated observed abnormalities associated with alcohol intoxication. The service staff are not police officers trained to conduct scientifically validated examinations to determine a greater than not probability of intoxication. Nor does the staff have the legal authority, or quite frankly the knowhow, to require patrons to participate in a standardized field sobriety test. This simplifies the standard of care to that of a reasonable and prudent person whose observations and/or interactions with the subject should identify the abnormalities association with intoxication.

This gatekeeping function relies on the knowledge and diligence of the establishment’s staff. The conflict arises when the staff that the licensee and the state are relying on to prevent over service rely principally on monetary tips from the patrons purchasing and consuming the alcoholic beverages. This creates a disincentive to “cutting someone off’ at an appropriate time, because patrons who are cut off and ejected almost never leave tips.

A reasonable and prudent policy should require that the establishment compensate the affected staff fifteen percent of the ejected patron’s tab. This, in part, demonstrates the establishment’s efforts to prevent the over service of alcohol.

The Transforming Restaurant - Some restaurant/bar establishments seek to maximize profits by transforming from a restaurant into a nightclub around 10PM and then staying open until last call. This transformation flips the percentage of revenue from 60%-80%: food and 20%-40% alcohol during restaurant times to 80%-100%: alcohol and 0%-20% food during the time as a nightclub.

In the transformation, tables and chairs get moved to the side of the room opening a dance floor. This reduces the available seating and increases standing capacity.

A band or DJ are often hired and frequently set up a sound system that is as loud as a jet engine and equipped with a bone jarring mega bass.

Sometimes portable bars are wheeled out of storage to provide additional sale and service points. The portable bars are frequently placed “near an electrical outlet” without regard to fire code entrance / egress requirements, the ability of bar backs to service the bar or the proper lighting to allow for interaction of customers and staff.

The number of waiters/waitresses usually decrease. The number of bartenders and bar backs usually increase. The wait staff will frequently transform from an appropriate restaurant uniform into something a bit more provocative.

Security staff must be dramatically increased to perform duties not normally associated with a restaurant. For example:

- Increased foot traffic at the entrance that must be evaluated for suitability to enter,

- Determination if the patron is of legal age to consume alcohol?

- Determination if the patron is exhibiting indicators of intoxication attributable to alcohol or drug use?

- Identification and deterrence of potential criminal elements (e.g, prohibiting the display of gang colors, motorcycle gang jackets, scanning for concealed weapons, etc.)

- Determination if the patron has been banned from entering?

- Collection of a cover charge

- Identification of any exiting patrons who exhibit signs of intoxication and take appropriate action.

- Interior security

- Observe the patrons to detect, respond to and defuse potential problems including proper ejection from the premise

- Coordinate with service staff in identifying patrons exhibiting signs of intoxication and handle the ejection from the premise

- Detect potential underage patrons who may have made it through the front door security and eject if necessary

- Identify and coordinate with service staff to promptly remove empty bottles from patron areas and clean up any spills

- Coordinate with service staff and all other security to safely dismiss patrons at the close of business. Ensure that all patrons have exited the premise.

- Coordinate with police, fire or EMS in response to an on-premise emergency

- Exterior security

- Coordinate with other security in the proper ejection of any patrons

- Maintain order of persons in line waiting to enter.

- Maintain order of patrons exiting the premise and leaving the area immediately around the premise

- Ordering a taxi or ride sharing service and/or assuring safe rides

The business plan for offered services, regulatory compliance proper staffing and profitability are very different between the restaurant and the nightclub. In addition, the business activities and their impact on the surrounding neighborhood are dramatically different. While restaurants often enhance a neighborhood, a nightclub that has not factored into its business plan the impact its operations will have on its neighbors is often a catalyst of nuisance bar complaints. The establishment has modified its original business plan of primarily a restaurant that provides alcoholic beverages during a meal to one where the goal is to maximize its profit through the sale of high margin alcohol during the remaining hours until mandated closing - what could possibly go wrong? Such a practice requires that the licensee and their management are diligent in effectively addressing the differences in business models in order to remain compliant with the regulatory scheme and a beneficial neighborhood business.

Promoters, Bottle Service - The term “club promoter” describes an independent contractor, (single person or company) hired by a nightclub to promote events, parties, concerts, gatherings, celebrity appearances and more. This person or entity is compensated: per head, by door percentages (cover-charge), revenue sharing, or perks and benefits. The bottom line, the more people in the door- the more money to the promoter.

Promoters are infrequently licensed by the alcohol regulatory body, often not registered or licensed businesses. They have historically been accused of promoting prohibited activities (e.g., beer pong drinking games, Jell-O shot consumption contests or girls gone wild contests). The promoter has little ability or desire to ensure that the crowd they draw to the establishment is, for example, the legal age to consume alcohol or do not over-indulge. Some promoters cater to specific gang affiliations, and the crowds they draw have proclivities of violence to outsiders.

An establishment that uses the services of a promoter must never relinquish to them any segment of control over the operation of the business. To do so often results in administrative and/or civil tort exposure against the licensee in addition to long term damage to neighborhood relations.

Shot Girls – Are independent contractors, frequently hired by nightclubs and/or adult entertainment venues. They are frequently compensated only upon the number of shots they sell to patrons and the tips they receive. Frequently, they have not received industry best practice training to detect underage and over-served patrons. And, based upon their compensation, have little interest it the licensee’s gatekeeping responsibilities. All too often the shot girls are allowed by the licensee to act outside of the regulatory scheme to prevent the service of alcohol to underage and patrons who exhibit signs of intoxication., such as convincing the patron to purchase multiple shots, or buying a shot for her (such shot usually do not contain alcohol). However, the licensee is ultimately responsible for the actions of these folks as they ply alcohol to patrons on the licensed premise.

In the post COVID-19 shutdown world, the significant new business practices will revolve around the mandated safety issues of serving patrons during a pandemic. The issues I outlined must still be considered in the establishment’s business model and reasonable, prudent steps be incorporated to prevent their occurrence. There is no doubt the great re-start will try the ingenuity and resourcefulness of the hospitality industry. I look forward to returning and toasting your success.

___________

About the author:

John Cocklin enjoyed a thirty-four-year law enforcement career with the Office of the New Jersey Attorney General – twenty-two as a detective, Lieutenant, Deputy Chief and Chief with the office’s Division of Criminal Justice and twelve as Chief Investigator with the office’s Division of Alcoholic Beverage Control (the State alcohol regulatory and enforcement agency in New Jersey) .

As Chief Investigator for the New Jersey Division of Alcoholic Beverage Control (NJABC) Mr. Cocklin was involved in the supervision of over 17,000 investigative activities and regulatory oversight of more than 10,000 businesses licensed to manufacture, distribute, sell or serve alcoholic beverages. As a member of the NJABC executive staff, he was involved in the State’s alcoholic beverage administrative rule making process. Mr. Cocklin received an Exceptional Service Award from the New Jersey Attorney General for his work in the NJABC’s Last Drink Initiative, which collected information from more than 530 municipal, county and state law enforcement agencies regarding the location of a person’s last drink before they were arrested for driving while impaired. Data were used to identify patterns of customer over-service at retail alcohol establishments

John Cocklin’s twenty-two-year tenure with the New Jersey Attorney General’s Division of Criminal Justice culminated in his promotion to Chief of Detectives. Mr. Cocklin had overall supervisory responsibility for 400 Detectives and Investigators assigned to various criminal investigation units in the Division of Criminal Justice (NJDCJ), the Office of the Insurance Fraud Prosecutor, and the Office of the State Medical Examiner. He was a commanding member of a team of NJDCJ, State Police Detectives, and Deputy Attorneys General that established the first Statewide Attorney General’s [Police] Shooting Response Team. As a Deputy Chief, he commanded the Division’s Internal Affairs unit and the Prosecutor’s Supervisory Bureau involving the supervision and review of criminal conduct, non-criminal professional conduct, use of force, and code of ethics violations involving the 3,800 investigative and prosecutorial personnel of the NJDCJ, New Jersey’s 21 county prosecutor’s offices and the New Jersey Police Training Commission authorized police training academies. As a detective, John was assigned to the Division’s Organized Crime and Racketeering Bureau, Statewide Narcotics Task Force, Economic Crimes Bureau and Medicaid Fraud Bureau.

For the past several years Mr. Cocklin has been a much sought after expert witness for both Plaintiff and Defense Counsel engaged in Dram Shop and other alcohol-related litigation. Most recently, Mr. Cocklin has worked with a team of technical experts employed by Exigent Forensic Consulting #Exigent-Forensics and @JohnCocklin

Mr. Cocklin holds a Bachelor of Science in Criminal Justice, a Bachelor of Science in Accounting and a Master of Business Administration. He is a Certified New Jersey Public Manager and a twenty-five-year certified New Jersey police instructor. He held additional certifications from the New Jersey Police Training Commission as a Firearms Instructor, Subgun Instructor and Rangemaster. John is a National Rifle Association-certified Range Safety Officer.

[2] States use different terminology such as: visible intoxication; obvious intoxication; apparent intoxication; actual intoxication; and, signs of intoxication. All the terms describe behavior that fall into three broad categories: (1) decreased inhibitions; (2) psychomotor impairment; and, (3) cognitive impairment (Brick- 2017)

[3] TIPs (Training for Intervention Procedures) On-Premise training, Health Communications, Inc. Arlington, VA

|

|

|