Rimkus Transportation Forensic Services

Industry-leading Expertise

May 2023 • Source: Rimkus

Utilizing state-of-the-art technology and proven methodologies, the Rimkus Transportation Forensics team provides a comprehensive approach to accident reconstruction, injury biomechanics, fire causation, product liability analysis, and materials testing. Rimkus clients can count on thorough examination and documentation, clear communication, and answers to complex questions.

|

The “right tools for the job” are paramount, and Rimkus has a vast array of tools in their toolbox.

|

Strategically located offices and experts across the country allow the Rimkus team to respond quickly to accident scenes. Rapid response to the scene is vital, as vehicles may be moved and roadway evidence can disappear or be impacted by weather, further complicating the reconstruction process.

Rimkus consultants can document site conditions, examine vehicle damage characteristics, inspect mechanical/electrical systems, and preserve hard evidence. Their experts can analyze the specifics, such as speed and direction of the vehicles, force of impact, skid-mark lengths, line-of-sight, road conditions, traffic controls, and other pertinent data, to determine the facts of the case.

About Rimkus

Rimkus is a worldwide provider of engineering and technical consulting to corporations, insurance companies, law firms, and government agencies.

Our experts specialize in forensic consulting, dispute resolution and construction management services, solutions for the built environment, and human factors support for the consumer, industrial, and healthcare industries.

Since 1983, Rimkus professional engineers, architects, scientists, and technical specialists have been recognized for their commitment to service excellence by local, national, and international business communities.

For more information, please visit www.rimkus.com or contact DeShaune Williams, VP Business Development, at 714-329-5639 or [email protected]. |

In Dealing with Field Failure of Plastic Building Products

May 2023 • Source: Jack Huang, Senior Scientist, and Andrew Schmit, Assistant Technical Director, Envista Forensics

Plastic is all around us. It’s in the clothes we wear, the electronic devices we use, the vehicles we drive, and even the concrete we walk on. Given the abundance of use, it shouldn’t be surprising that plastics are also used in building products, including pipes and fittings used for potable and processed water.

When it comes to the failure of plastic components, especially those carrying water, the resultant damages require the need to identify the exact cause of the failure as the root of the failure will be critical to multiple parties, e.g., the building owner, insurance companies, the manufacturer, and the installer. In any of these cases, there are a number of potential causes that must be considered.

First of all, the material choice likely comes to mind as the most intuitive suspect for the source of the problem. Subsequently if informed that a failed product is made with plastics, the idea of plastics being a lower quality substitute to their metallic counterparts is a common misconception held by the non-technical public, including juries. The fact is, contrary to conventional wisdom, plastics can and might be the right/best candidate for many engineering applications. After all, plastics far outperform metal in a variety of harsh service environments. They are also more lightweight and can be easily manufactured into highly complicated geometries.

Plastics, or technically polymers, are conglomerates of organic chains consisting of large numbers of repeating hydrocarbon subunits; imagine long chains made with ball-and-socket links. Therefore, understandably, the chemical makeup of the subunits (choice of ball-and-socket links), the number of repeating units (length of chain), and the way the chains are packed together (random or ordered) will all influence the observable properties of the resultant polymer chain conglomerates, e.g., mechanical strength, chemical resistance, processing ease, etc. The continued trend of increased use of plastics in many engineering and structural applications is the result of availability of many choices of the repeating unit (versatility) and the abundance of hydrocarbons from petroleum refinery process for raw materials (cost).

To elucidate the richness of plastics and its utility, here are some of the most frequently utilized plastics in building products:

PEX

PEX stands for cross-linked polyethylene. Polyethylene is the simplest hydrocarbon available and consists of just carbon and hydrogen atoms. It is flexible and is normally used for articles such as grocery bags. When cross-links are introduced into the structure, it is equivalent to introducing cross-stitches between straight yarns, and the restriction in movements makes PEX both structurally stronger and more chemically resistant. Over the past two decades, PEX has gained tremendous popularity as a residential water supply piping material. However, the increased use has not come without downsides. When PEX is used in aggressive environments, like supply lines for chlorinated water, negatively charged chloride ions act as an oxidizing agent and can cause degradation of the PE polymer chains. To extend their life, PEX pipes require the addition of antioxidants to help stabilize the PEX material. Continuous exposure to chlorinated water will ultimately lead to degradation of the PEX supply lines until eventual rupture.

PVC/CPVC

PVC/CPVC are the chlorinated version of PE, meaning chlorine atoms are now incorporated onto the main carbon chains to replace some of the hydrogen atoms. With the addition of chlorine atoms on the main chain, it adds stability to the polymer chain due to the extra electrons that chlorine atoms carry. Additionally, the chlorine atoms surrounding the carbon main chains are larger atoms than the hydrogen atoms and therefore offer better protection of the chains from attack. This makes PVC and CPVC excellent choices for sanitary sewer applications and water supply piping, whether buried or above ground. However, in some service environments, problems still do occur.

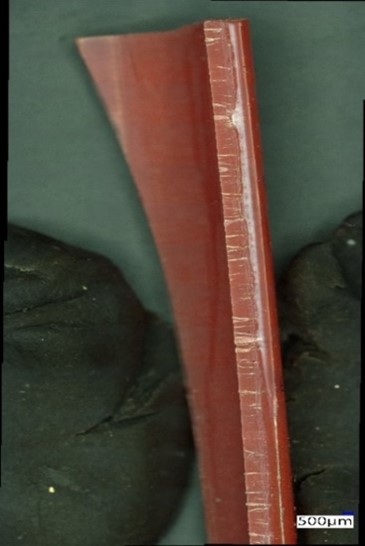

PVC/CPVC is generally not recommended for use with most solvents (soluble or insoluble) including ketones, ethers, furans, esters, alcohols, and aromatics. The solvents can be absorbed into the CPVC substrate and lead to softening of the CPVC pipe. Cases of CPVC pipes used for fire suppression systems have been reported to fail due to accidental contact with drywall sealant or an anti-freeze agent that contains esters. Polyolester (POE) oils are another contaminant that can result in the degradation of CPVC pipe. While POE oils are not a typical constituent of domestic water supplies, remnants of the oil can sometimes be found within iron pipes or heat exchangers. It has been observed that, even at low levels, POE oil can lead to progressive cracking failures within CPVC pipes (Photograph 1).

Photograph 1: Interior cracking on CPVC joint exposed to POE oil Photograph 1: Interior cracking on CPVC joint exposed to POE oil

POM

Polyoxymethylene (POM), also known as acetal, polyacetal, and polyformaldehyde, is an engineering thermoplastic due to its high crystallinity. It is therefore commonly used in precision parts requiring high stiffness, low friction, and excellent dimensional stability, such as supply line nuts and complexly shaped fittings. However, acetal resins are sensitive to acid hydrolysis and oxidation agents such as mineral acid and chlorine. Low levels of chlorine in potable water supplies (1–3 ppm) can be sufficient to cause environmental stress cracking, a problem experienced in both domestic and commercial water supply systems. Refrigerator filters, pipe/tube connectors, and faucet components are also common POM parts that have exhibited ESC due to exposure to chlorinated water.

TPE

Thermoplastic elastomers (TPE), sometimes referred to as thermoplastic rubbers, are a class of copolymers or a physical mix of polymers that consist of materials with both thermoplastic and elastomeric properties. While most elastomers are thermosets (plastics that don’t soften upon heating) and can’t be processed by injection molding, thermoplastic elastomers are relatively easy to manufacture by injection molding and other thermal processing techniques. TPE thus shows advantages typical of both rubbery materials and plastic materials and is frequently used where conventional elastomers cannot provide the range of physical properties needed in the product. Flexible thin-walled tubing and rubber roofing material are a couple of examples.

Field Failure Analysis of Plastics

Now that you have some introduction to commonly used plastic materials for building products under the belt, let’s look at how a field failure is approached next. In the world of failure analysis, when it comes to component failure, regardless of the material, metallic or non-metallic, four relevant factors are to be considered before any verdict can be derived, i.e., material selection, part design, manufacturing processes, and installation errors.

Material selection is without a doubt the number one task when it comes to developing any commercial products. On top of structural integrity requirements, application environment (likelihood of exposure to detrimental chemicals or not), expected life span, and overall cost target are the first level of considerations that will help define the probable material candidates. However, it is not unusual to see cases where cost target overrides the structural integrity and application environment requirements. Certainly, a landmine to watch out for when dealing with field failure cases.

Once the proper material is selected, then comes the part design. Achieving desired structural integrity in a component requires not only inherent material strength but also structural stiffness, which is geometry dependent like wall thickness. On top of wall thickness, sharp corners can cause stress concentration and lead to failure at lower than target nominal applied stress. Consequently, proper radiuses to avoid sharp corners and proper bottom thread design for effective thread engagement are some of the seemingly trivial yet critical factors to look out for in a failed part.

After proper selection of material and appropriate design considerations, plastic parts then get fabricated commonly via injection molding (with 3D geometry) or extrusion (tubing). Not surprisingly, proper fabrication process parameters will also impact the quality and end performance of the components.

Some of the critical processing parameters for injection molding are adequate raw material drying, molding temperatures, injection speed, mold design for efficient material flow path and mold cavity air venting, and lastly cooling speed to minimize residual stress. For extrusion, temperatures for different process zones, proper screw elements configuration for material to be processed, and extrusion speed are some of the important parameters to pay attention to. Localized stress concentration due to air entrapment associated with inadequate raw material drying and/or poor injection mold cavity air venting are regular issues encountered in injection molding. For extrusion, premature material degradation frequently happens due to improper processing temperatures and/or excessive mechanical shearing imposed on the material by incorrect configuration of the screw elements. Therefore, signs of air bubbles, localized defects, and lower than projected material properties are always something to keep in mind when processing mistakes are suspected.

Lastly, even if everything associated with producing the parts has been handled correctly, installation errors could wipe out all the good efforts leading up to the final step of the project. Overtightening (over-torquing) is the most common mistake encountered in field failure of plastic parts. Installers who are accustomed to installing metal fittings have the tendency to apply the same rules in connecting plastic fittings, especially if the installation involves a male metal component threaded into a plastic female component. Failure at thread bases of the plastic components is the most observed field occurrence. Another installation error involves accidental unintended exposure of plastic parts to detrimental chemicals. CPVC pipes coming into contact with anti-freeze agent containing polyester or POE oil from heat exchangers are good examples of this category.

So, it is always good practice to consider the four factors before rendering any conclusion. But, sometimes, even after taking into account all of the factors, exceptions can still occur. One good example entails PEX water supply pipes. ASTM (American Society for Testing and Materials) Standard F876 establishes the performance requirements for PEX pipes. PEX manufacturers whose products pass the F876 requirements normally warranty their products for at least 25 years of field life. Yet, periodic chlorine spikes in potable water and local water quality could still lead to premature failure of the PEX supply lines. Photograph 2 and Photograph 3 show a PEX pipe degrading over time in a chlorinated water environment. One can see the initiation and propagation of longitudinal cracks due to environmental stress cracking. The hydrostatic water pressure intermittently applied on the pipe, coupled with the chlorine attack, has then caused the inner surface to develop surface and through-thickness propagating longitudinal cracks on the pipe. The sad reality is the pipe has been in the field for less than 10 years.

|

Photograph 2 - Longitudinal cracks on inner surface of PEX pipe

|

Photograph 3 – Opened longitudinal cracks Photograph 3 – Opened longitudinal cracks

|

Finally, to sum it all up, failures of building products, plastics or not, contribute to billions of dollars in losses every year. Even though something like a failed pipe causing a water leak may seem like a simple investigation on the surface, the actual underlying cause of the failure may be complex and involve many contributing causal factors. Therefore, it is important for you to have the right forensic experts on your team with the right testing capabilities to ensure an accurate investigation so you can understand and be able to cover all facets of the failure in your case. |

Defending the 30(b)(6) Corporate Representative Deposition and the Reptile

Source: May 2023 • Joseph W. Pappalardo, Esq, Gallagher Sharp LLP & Matthew A. Smartnick, Esq., Gallagher Sharp LLP

The Rule

Rule 30(b)(6) applies to depositions of both party and non-party corporations, requiring that the noticing party issue a subpoena to non-party deponent corporations. The rule has two requirements: the notice must describe with "reasonable particularity" the matters for examination, and the designee must testify about information known or reasonably available to the organization. As regards the latter, the designee must make reasonable inquiry within the organization and the organization must educate the designee. Once the corporation has designated a deponent on a particular issue, it becomes bound by the designee's testimony, which may be used "for any purpose" at trial, regardless of whether that individual is available to testify. A Rule 30(b)(6) deposition does not foreclose a deposition by any other procedure under the Federal Rules.

Notice Requirements

The notice required by Rule 30(b)(6) must provide the date, time, and place for taking the deposition, specify the name and address of the entity being deposed, set forth the matters for examination with reasonable particularity, indicate the method by which the testimony will be recorded and whether documents are sought, and be accompanied by a document request or formal Rule 34 request for the production of documents. A corporation's Rule 30(b)(6) witness should be deposed in the district of the corporation's place of business, "subject to modification, however, where justice requires." Plaintiff’s attorneys sometimes try to depose a corporate representative at company headquarters or other sensitive locations, but a motion for protective order should be considered.

A protective order should be granted by the court when the moving party establishes "good cause" for the order and when justice requires a protective order to protect a party or person from annoyance, embarrassment, oppression, or undue burden or expense. The court will consider the facts, select the place of examination, and determine what justice requires with regard to payment of expenses and attorney fees. Unlike a deposition notice pursuant to Rule 30(b)(1) for the deposition of other witnesses, the Rule 30(b)(6) notice must describe with reasonable particularity the matters to be examined, and objections should be made immediately if a notice is unclear.

Defendant's counsel should respond to each area of inquiry with detailed and thorough objections where necessary, including objections to proportionality, relevance, materiality, broadness, harassment, mental impressions of counsel, matters in the province of experts, and matters for which there is no corporate knowledge. It is common and best practice for opposing attorneys to meet and confer on all of these issues prior to the deposition.

Limits on the Deposition

A Rule 30(b)(6) deposition is treated differently from other depositions for purposes of the Federal Civil Rules 10-deposition rule. Where a corporation designates multiple designees to testify on different topics, each designation will count as a separate deposition. A Rule 30(b)(6) deposition should be structured to address questions related to the claims at issue. The reasonable particularity standard means that the requesting party must designate specific areas that will be investigated, and broad or generic notices are not sufficient.

Deponent Corporation’s Duties

When a corporation receives a Rule 30(b)(6) deposition notice, it must designate one or more witnesses to testify and educate them on the matters for examination. The designated representative(s) do not need to be the person most knowledgeable- “PMK” -about the matters (the PMK concept is often misunderstood), but must be able to provide binding answers on behalf of the corporation.

The purpose of the Rule 30(b)(6) witness is to represent the collective knowledge of the corporation, and not have the witness testify to the designated witness’s personal opinions or beliefs. The designated individual may and will likely need to review materials and meet with people from within the organization to become educated enough to speak for the corporation. The witness can be examined on the corporation's opinions and beliefs.

The designated witness must be qualified to testify and must answer the questions, unless the area of inquiry is not within the knowledge of the corporation, is privileged, or is harassing. In some cases, more than one corporate witness may need to be presented, but careful preparation and coordination is key in such situations. If possible multiple deponents should be avoided to minimize the possibility of inconsistent testimony.

Generally speaking, an answer of “I don’t know” by the corporate representative during the deposition is not an adequate response.

Thus, one of the most important tasks is choosing the correct deponent. Simply relying upon “legacy” witnesses because they have testified so many times is not advisable. Counsel and the corporate defendant need to carefully evaluate who is the right person for the particular deposition, who makes the best witness, and who can most effectively express the corporation’s position.

Counsel for the corporation should be careful to adequately and repeatedly prepare the corporate representative prior to the deposition to make sure the individual is adequately prepared to testify as to matters reasonably known to the company. This is not the time to cut corners. Preparation sessions should include uncomfortable mock cross-examination, possibly outside witness training, videotaping of preparation sessions. Insurance companies should be aware that a 30(b)(6) deposition is, more than most depositions, a potential game-changer and can be a risk for a nuclear verdict.

The Reptile

As is well known by now, a major and dangerous aspect of preparing a Corporate 30(b)(6) involves recognizing and neutralizing a Reptile claim.

The Reptile Theory is a trial strategy used by plaintiffs, based on the 2009 book "Reptile," which relies on invoking fear and danger reactions in jurors. The theory argues that the defendant's conduct poses a danger to the jurors, their family, and the community and that a jury verdict is the only way to prevent that. The authors of the Reptile claim over $7 billion in settlements and verdicts and have created an entire industry of books, seminars, and publications. The theory appeals to the fear and emotional sense in jurors without actually calling out the "Golden Rule," which is almost universally disallowed in courts.

The Reptile seeks to convince jurors that no harm is acceptable, no risk is acceptable, and all risk can result in catastrophic results. Jurors are persuaded that defendants must eliminate all risk and follow all safety rules, no matter how unrealistic that may be. The community suffers because the danger imposed by the defendants is imminent and ubiquitous, and if the community is at risk, the jurors and their families are at risk.

There is solid neuroscience which supports the Reptile theory, focusing on the "subcortical" part of the brain, which consists of the brain stem and amygdala. These portions of the brain are primitive and respond and react to threats and fear, invoking the fight or flight response. Reactions are involuntary, automatic, and not reasoned. The Reptile theory seeks to tap into these primitive unevolved brain instincts.

The Reptile's unevolved primitive brain's corollary or opposite is the idea that jurors should rely upon their "primate" evolved brain. The primate brain relies upon the frontal lobe and frontal cortex anatomy, appealing to logical reasoning and cognitive judgments that we use in our civilized society. The anti-Reptile asks the juror not to be fooled by being scared or made afraid and to decide the case based upon civilized societal norms.

To counter the Reptile argument, preparation is paramount. There should be at a minimum two pre-deposition meetings to prepare the corporate representative. It is essential to show that the corporate records, especially those required by regulations, are well kept. Compliance with federal law and the pre-employment investigation and post-employment training and recurrent training of drivers is critical. Before deposition preparation, the corporate representatives' cross and direct examination must be fixed, and all of the pre- and post-accident documents have been generated.

The corporate representative should never admit open ended safety questions such as “no risk is acceptable”, “all harm must be eliminated”, and “violation of safety rules endangers the community.” The witness must force opposing counsel to be specific about the facts of this accident and not open ended generalizations. Plaintiff's counsel must be forced to define “safety” and of course the witness should never admit that trucks are “less safe”, that they are harder to maneuver, brake, steer, that they are dangerous, or that truck drivers are professionals like doctors or lawyers, and so forth.

The witness must keep bringing the focus of the deposition back to the facts of this accident. Instead of admitting that the actions of the driver and the company were inevitably unsafe, the witness should be prepared to distinguish between facts of the accident which are relevant as opposed to irrelevant facts.

Instead of open ended yes or no responses, the witness should be encouraged to respond "not necessarily" to open ended questions about safety.

All corporate deponents must be prepared on, and know, what was said in prior depositions. To the extent it is truthful and can be supported corporate witnesses should be consistent in their responses. Again, national discovery counsel or a specific in-house program regarding depositions should be considered.

In summary, the Reptile Theory is a powerful and effective technique used by plaintiffs that relies on invoking fear and danger reactions in jurors. While it has its controversies, there is solid neuroscience that supports the Reptile theory. To counter the Reptile argument, it is essential to show compliance with federal law and to have all pre- and post-accident documents ready. The primate brain appeals to logical reasoning and cognitive judgments that we use in our civilized society, and decision-making should be based on reason, not fear.

Key Takeaways

Although nothing can guarantee the elimination of dangerous deposition testimony or resulting high verdicts, the techniques described here will help the defense lawyer and corporate representative properly prepare for a 30(b)(6) deposition as well as how to recognize a Reptile claim and how to counter it. Here are the key takeaways:

1. The Reptile Theory is an effective and dangerous technique for increasing damages. Careful recognition of it and the physiology upon which it is based are crucial to proper corporate representative preparation.

2. The corporate policies, documents, and actions required by FMCSRs are key attack points for the Reptile. The corporate representative and defense counsel must be intimately familiar with them and how to best describe them in a deposition.

3. Corporate representatives must recognize key Reptile terminology and not fall into the trap of answering open ended questions about safety, danger, eliminating risk, and needlessly endangering the community.

4. Frequent and intense preparation is a key. Never should a defense lawyer scrimp on proper preparation, mock cross-examination, and intense document review. At least two to three deposition preparation sessions are crucial for any corporate representative.

5. A formal program, in-house or through national discovery counsel, should be considered to provide consistency of responses to paper discovery and deposition examination.

|

Looming Collisions

May 2023 • Source: Exigent

In many rear-end collisions involving a vehicle that is stopped or moving slowly in the lane of travel, it is common for the driver of the striking vehicle to say that they did not realize the lead vehicle was stopped or moving very slowly until it was too late to avoid the crash. Drivers in these situations ] likely experienced a phenomenon called “looming.”

Human factors experts address the issue of looming in vehicle collision cases to determine whether the driver perceived and responded to the slower moving orstopped vehicle in a reasonable amount of time and whether the driver’s actions were a cause of the crash. Read the full article. |

|

|